I-69, Southern Indiana, and the Power of Vision

“Our region is sinking into oblivion,” noted one Daviess County local 20 years ago. Back then there was no $100 million WestGate@Crane Technology Park, no direct interstate access to the $2 billion Naval Surface Warfare Center (NSWC) at Crane, no ROI Master Plan for development. No state READI funds. And certainly no I-69. Employment and investment numbers were all in the red zone. People were quietly leaving for better opportunities elsewhere.

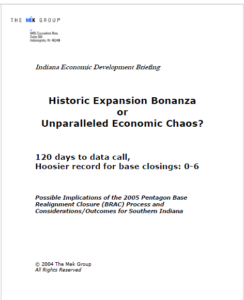

BRAC threatened regional viability

Formal research and interviews conducted by MEK in 2004 revealed a dark pall over the region. The then-active federal Base Realignment and Closure process (BRAC) was widely expected to seriously drain off critical high-paying jobs, perhaps even the unthinkable: closing the massive NSWC Crane facility itself. After all, that had nearly occurred in the 1995 BRAC process. A fearsome economic catastrophe was potentially brewing.

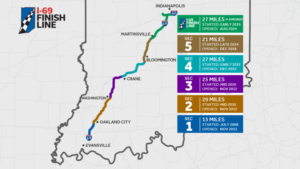

Fast forward to August 6, 2024: an unexpected $4 billion and two decades later, Gov. Eric Holcomb stood on a new I-465 ramp opening the final section of I-69 between Evansville and Indianapolis. On that momentous day, Gov. Holcomb publicly declared that with the opening of the long-awaited 465 access, Hoosiers and visitors alike “will be able to use something that’s only been dreamt about. There were a lot of cynics along the way, a lot of doubters that understandably wondered if it would be completed in their lifetimes.”

“No project is too big”

“Today, “ the governor proclaimed, with former Governors Mitch Daniels and Mike Pence looking on, “we proved that no project is too big.”

What happened in the interim to make any of this possible? What key lessons can be gleaned to inform and create future far-reaching initiatives?

Over the years a vision of what could be was carved out and shared among some key influencers, all of whom played a cumulative role in setting the stage for transformation. There were many dimensions and influencers who worked tirelessly exploring different options for I-69 construction and related development of what is now a $100+ million tech park southwest of Bloomington. This story recounts a few highlights of what it takes to make a difference.

After thousands of tons of concrete have been poured and asphalt laid across southern Indiana, it might be hard to believe that back two decades ago, it was widely thought that if I-69 ever came into existence, there was a good chance of it being a mere “Super 2” upgrade sliding up the westside of the Hoosier state into Terre Haute and I-70. Perhaps surprisingly, an environmental impact report was underway for an as-yet-unfunded all-new terrain build of I-69, one that would graze the endangered Naval base. Many thought it a waste of tax dollars.

But there was a purpose, even minus any meaningful funding for road construction. The state powers-that-be thought the presence of at least exploring an interstate connection might improve the BRAC score and perceived military value of NSWC Crane, perhaps helping to lead federal officials to keep the doors open and the jobs with it.

David Graham, a grandson of a successful family of entrepreneurs in Daviess County, led and partnered with a multitude of elected officials and community leaders over several years to fashion a vision of access and opportunity for southern Indiana. The effort was detailed in a wide-ranging Wall Street Journal-recommended book, I-69 – the Unfinished History of the Last Great American Highway. The author credits Graham with “the idea of building an interstate highway connecting Evansville with Indianapolis,” a concept and vision that was taken up, embraced and supported by many.

Inflection point for a long-time dream

Tracing the development of I-69 across several states, author Matt Dellinger pinpoints a private breakfast as the inflection event for southern Indiana. Dellinger opens his book with the story: “David invited two friends, David Cox, with the Daviess County Growth Council, and Jo Arthur, with the Southern Indiana Development Corporation, to meet David Reed who was conducting an economic development study for the Hudson Institute on the potential for development in southern rural Indiana.”

The Hudson Institute, founded by Herman Kahn and others in New York, had moved to Indianapolis in 1984 with help from the Lilly Endowment. At the time of the private I-69 breakfast, the think tank was headed by then-future Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels, who had previously served in the Reagan Administration.

The seeds of a connecting interstate to revitalize the region had been planted.

However, as MEK qualitative and quantitative research confirmed back then, few expected the interstate to be funded and built in their lifetime, probably never.

The region had already experienced the loss of another interstate through the region: I-64. That project, as this author was told, was the victim of political intrigue, as original plans inexplicably shifted from Vincennes through Washington and points east, dropping down south closer to undeveloped (and costly) hilly terrain north of Evansville. It was a great disappointment, with state funds expended in Illinois and Indiana for nascent dual lane roads and bridges that went nowhere.

The odds of I-69 ever being built were so slim, as one attorney from McHale, Cook, and Welch (now Dentons) told me, that some of proposed “plans” for the non-existent interstate were made to deliberately cut straight through the Lugar family farm on its “path” to 465. The inside political “joke” served up by the Democratic gubernatorial administration, as the attorney related, was not lost on U.S. Senator Richard Lugar, a prominent Republican. Of course, the route was later substantially altered.

In related developments of the day, an underfunded Certified Technology Park policy program had been fashioned inside of the old Indiana Department of Commerce under the O’Bannon and Kernan administrations, but there were no plans at the time to expand it to the NSWC Crane area.

What did things look like? Back 20 years ago, there was no federal $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. There was no $50 billion CHIPS Act. Thankfully, Lilly Endowment had successfully launched the transformational and visionary “Giving Indiana Funds for Tomorrow” (GIFT) program in 1990, establishing and funding community foundations across the state. That far-reaching program continues to positively lift up major opportunities, including the southern Indiana region served by I-69. An initial Endowment investment of $100 million has grown to more than $3.7 billion in combined assets statewide.

Twenty years ago, there was no Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC). There were no federally or state-funded ecosystems anywhere near the scale of what takes place today.

Broke with a crippling deficit

In fact, Indiana was basically broke. The state fiscal coffers were bare. The state actually had a $700 million deficit at the start of 2005. It owed millions of dollars to area schools across the state.

In 2004, public funds and money in general were in short supply.

So how did any of this get done?

As plans for a possible I-69 continued to be debated, other developments took place with locals leveraging resources. After the NSWC Crane base nearly shuttered its doors in 1995 (with key work from Louisville being peeled off for other centers), numerous initiatives in southern Indiana commenced a nascent rise. It was economic life or death, minus significant federal or state support.

Other Hoosier federal defense facilities were not so fortunate. The one million sq. ft. Naval Air Warfare Center (NAWC) with some 3,000 employees on the east side of Indianapolis was closed down as a result of the 1995 BRAC, its facilities privatized.

Some key NAWC administrators and engineers migrated down to the NSWC Crane facility, which had largely been spared the BRAC axe. New efforts to focus and sharpen NSWC Crane’s operations rose up, with the facility creating new jobs and attracting high-level technology professionals and engineers, so much so – as the anecdotal story goes – the southern part of Bloomington and eastern Greene County exploded with fresh economic growth from talent moving into the area.

A center of innovation revives

Remembering a once vibrant economic past, people in Washington, Indiana wanted to create new opportunities. Many remember when Daviess County was a high-impact growth region, even stretching back when it scored a major economic win with the “Shops,” a massive repair facility for the B&O Railroad. Innovation was the local byword with the Graham Brothers designing and building some of America’s first utility vehicles and trucks.

Twenty years ago, much of that had vanished. Cracked, decaying old buildings dotted the once-vibrant downtown. The population – including promising young graduates – was declining precipitously.

While many people and groups across southern Indiana worked to stoke the development fires for a possible I-69 development, people in Washington also quietly went to work.

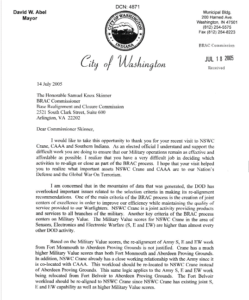

The surprise re-election of a former Mayor, David Abel, served as an unexpected catalyst. Defeated in a prior election, the new Mayor was determined to make a difference. He had built a successful investment business and knew the city’s fabric well.

Partnering with Ron Arnold, the then-executive director of the Daviess County Growth Council who had succeeded Dave Cox (soon to be renamed the Daviess County Economic Development Corporation), the Mayor joined forces with our firm and the Washington Times-Herald newspaper for a courageous foray of fact-finding.

A political risk

Despite significant political risk, the Mayor commissioned the Washington Vision and Values Project, stating publicly, “Many positive forces are at work in Washington, but there are also challenges to be faced and decisions to be made. Our community needs to share a clear vision that will guide us in the days ahead.”

Continuing, the Mayor noted: “The city has changed dramatically during my lifetime… We need to see where we are, where we want to go and how each person can play a role to create a vision we can work toward together.”

Continuing, the Mayor noted: “The city has changed dramatically during my lifetime… We need to see where we are, where we want to go and how each person can play a role to create a vision we can work toward together.”

Much of the Vision report published in the Washington Times-Herald newspaper was nothing short of ugly. Confidence in the future had all but drained away. Most people surveyed believed that the best days of the city and county were already in the rearview mirror.

But people were willing to give things a try – a new vision was shaping up. Although uncomfortable, Abel’s daring initiative to confront unpleasant facts was having good effect. Meanwhile, elected officials and community leaders in the surrounding area – especially in Greene and Martin counties – were exploring options.

A vision strengthened

On May 23, 2004, efforts reached a pivot point. Inside Indiana Business host Gerry Dick traveled to Washington and addressed a combined group of regional business and community leaders. The effect was electric. Local leaders heard how other regions had transformed and began to see new potential for regional assets like the NSWC Crane base.

The prior MEK Gatekeeper research had shown considerable interest by the Indiana Department of Commerce in exploring the possibility of a Certified Technology Park being established next to the NSWC Crane facility. Such a facility would likely be viewed favorably by federal officials evaluating the military value of the base for BRAC issues.

An issue-changing white paper

Based on the research, which included interviews with federal defense officials, planners, and economic development professionals, we at MEK produced a white paper on the opportunity. It unexpectedly went viral, appearing in forums and online publications across the defense and economic development spectrum. Independent interest spawned new coalitions and efforts, stretching up to Indianapolis and state agencies, as well as the General Assembly.

Beginning with the Daviess County Growth Council, formal application was made and certification sought. Joining the effort were officials and community leaders from Greene and Martin county, which shared borders and workforce with Daviess County and the physical boundaries of the $2 billion Naval facility. A tri-county steering committee was set up.

Concepts about a possible “Crane North Project” for defense contractors had been kicked around for a few years but had not advanced. Martin County controlled some acreage that included abandoned asbestos-laden buildings – this held promise.

The Southern Indiana Development Commission (SIDC) had been working on a possible brownfields grant for the Martin County property, which was immediately east to the possible Daviess County development region and southeast of Greene County. Efforts continued to move forward for the CTP application, and MEK secured endorsements from Purdue and Rose-Hulman officials as partners for the proposed park.

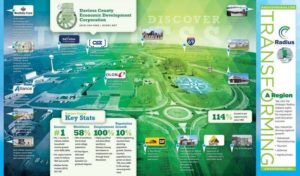

The WestGate is born

As the brownfields process continued and initial purchase options on bean and corn fields came into play, MEK crafted a compelling place-making brand to rally around: the WestGate@Crane Technology Park. Other quality of life and quality of place initiatives were planned and set in motion for Daviess County.

Daviess County scored the first approved Certified Technology Park designation for what would expand into Indiana’s first tri-county park. With local funding and a contractor in place, Daviess County launched the first building. MEK organized a media event to mark this first building of the WestGate, which event was led by then-Lt. Gov. Becky Skillman.

After delivering her remarks in the now-cleared Martin County space, the Lt. Gov. and guests walked across the road to Daviess County. There, on the edge of an undeveloped corn field, they broke ground for the first new building for a defense contractor.

After delivering her remarks in the now-cleared Martin County space, the Lt. Gov. and guests walked across the road to Daviess County. There, on the edge of an undeveloped corn field, they broke ground for the first new building for a defense contractor.

While the vision was quickly expanding into an initial reality back then, few could have guessed that in 2022, barely a few hundred yards away, a new group would be led by Governor Holcomb, breaking ground in 2022 for the WestGate One, a new $83 million microelectronics facility and campus.

During that time, Ron Arnold and I met with a skeptical Mickey Maurer and other IEDC staff, who were reluctant to commit additional funds and tax dollars to more unproven CTPs. He agreed to at least consider the possibility. After a pivotal meeting outside the NSWC Crane base with officials from the three counties, Purdue administrators, NSWC professionals, and defense contractors, the lights went on.

At a later groundbreaking for the WestGate Academy in the park in 2011, Gov. Daniels said (as reported in the Greene County Daily World) that the tri-county success of the WestGate park “pulls together so many threads of what we are trying to do to make a better state here. With I-69 there are a lot of reasons to see that project through. When I came listening to folks here (at Crane) I came to understand and believe deeply that the future growth of this facility (NSA Crane and WestGate Tech Park) was one of the top reasons to build it.”

The story continued, and now there exists a $100 million technology park that will soon basically double in size, all served by the $4 billion I-69 directly connecting Indianapolis and Bloomington with points south.

Sadly, Mayor David Abel, one of the primary architects and supporters of the vision that drove success, passed in 2015 without seeing I-69 or the revitalization of Washington fully come to fruition. But he never lost the vision and never gave up.

The same vision-sustaining efforts can be said of Washington Mayors Tom Baumert, Larry Haag, and Dave Rhoads, as well as long-serving former Loogootee Mayor Don Bowling and Authority leaders Gene Shaw (now deceased), Kent Parisien, and John Mensch, as well as many others in the region.

What are the takeaways for crafting a successful vision? Of course there exist many takeaways from the hundreds of people and organizations who stepped up and made a difference over the past 20 years. But here are three:

A successful vision starts with an idea, but becomes data-driven

In southwest Indiana, many people and organizations intuitively knew that an interstate would help revitalize an area and help preserve the 6,000 jobs associated with NSWC Crane. How to get there was a different story. Different individuals and groups on various levels all had ideas and thoughts.

Research – especially including local and regional community leaders – conducted by various entities helped define opportunities and challenges. Key benchmarks were identified that helped guide regional, state and federal solutions.

In one dynamic meeting between leaders in Daviess, Greene and Martin counties in 2005, MEK hammered out a Memorandum of Understanding (actually originally handwritten in cursive) that summarized the needs and commitment of the officials. The MOU was widely adopted and became an important foundation to build upon.

A transformative vision requires bold steps and process

In 2004, various needs were identified, but funding was scarce to non-existent. Various options, including a P3 (public-private partnership) structure, were considered. Now Governor, Mitch Daniels accelerated the formation of the Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC), and also hit upon a unique idea.

Funds from the $3.85 billion leasing of the Indiana Toll Road in northern Indiana – itself an astonishing public policy innovation – could be used to design and build an all-new terrain interstate connecting Evansville to NSWC Crane, with plans to later push the interstate forward to Indianapolis. Importantly, the new I-69 would link NSWC Crane to I-64, an interstate that is known in some Navy quarters as the Norfolk Interstate. I-64 directly connects to the world’s largest naval station in Virginia.

Meanwhile, locally in Daviess County, DCEDC director Ron Arnold spearheaded an effort to create a local EDIT fund for economic development while simultaneously opting out of the state inventory tax, an artificial fund that discouraged development of supply chain related industries. Arnold also worked to create a foundation associated with the economic development group to assemble and leverage critical funds.

As the profile of the potential WestGate was deliberately elevated, other groups became interested, lending important support. Prominent intellectual property attorney Donald Knebel, a moving force of the popular New Economy – New Rules monthly gathering presented by the Barnes & Thornburg law firm, brought a team to Daviess County to discuss innovation, patent law, and development pathways. The vision continued to grow.

Following the example of the highly successful Cummins Research Park in Huntsville, Alabama (one of the world’s leading technology business parks associated with NASA), Arnold was able to work with local officials to buy property for the WestGate tech park and reserve it for future growth.

Even though Arnold is no longer with the economic development group, the fruits of that initiative continue to pay off with strategic expansion opportunities today. Other developers purchased property in Martin and Greene counties, designing and building facilities with multiple thousands of square feet.

The vision of a 750-acre dynamic tech park had come to pass, even before I-69 reached its gates. Today, more than 50 defense and related companies work in the park. The WestGate Authority, comprised of officials from the three counties, helps guide the park, supported by the Uplands Science and Technology Foundation. NSWC Crane itself today enjoys broad support “outside of the fence” from the Crane Regional Defense Group, as well as the IEDC defense industry group at the state level. Major developments in microelectronics, hypersonics, and other critical defense technology are underway in the park.

Purdue and Indiana University announced plans for new high-profile engagements in the park. The Hardtech Corridor initiative from West Lafayette to Indianapolis can now physically link to the WestGate, given unimpeded access on I-69.

The Bloomington-based Regional Opportunities Initiative significantly expanded planning and funding initiatives for the park, creating an all-new Master Plan and other critical strategic programs.

A successful vision requires unwavering support, even in the face of opposition

As is well known, the Evansville to Indy I-69 project faced numerous roadblocks, both political and financial. Figurative torches of support were lit up all over the region, including significant support from the Bloomington Chamber of Commerce and its Voices for I-69 advocacy group. As Governor Holcomb underscored on August 6, the I-69 project was one that had long once “only been dreamt about.” The Governor acknowledged that “There were a lot of cynics along the way, a lot of doubters that understandably wondered if it would be completed in their lifetimes.” Despite the doubters, the stage is now set for an entirely new generation of economic development and opportunity.

Unfailing and vibrant early support from Governor Daniels, southern Indiana leaders like David Graham, Mayor Dave Abel, Jo Arthur and Greg Jones of SIDC, Ron Arnold and the County Councils and Commissioners (including redevelopment leaders and legal counsel), as well as Mickey Maurer and Nate Feldman (then of IEDC), Steve Gootee of NAWC and SAIC, developers Dale Ankrom and Kevin Bush, and others at the state level, all collectively made a difference. Smithville weighed in with a project-saving high-speed fiber connection for WestGate’s first defense tenant. Several county-level and regional staff made critically important contributions to help catalyze the emerging vision, including Darla Miles of DCEDC.

Many more too numerous to be named in this brief recounting contributed in strategic and important ways (and apologies to any left out – this post is certainly not a comprehensive history). Success continues and has been significantly intensified through new generational leadership and opportunities, including the aforementioned Regional Opportunities Initiative strategic engagement.

Despite opposition and fierce challenges, torches of support were passed up through the years. And on August 6, 2024, the capstone of many years of effort and connected projects came to fruition.

Today, the $4 billion I-69 connects Evansville to Indianapolis, a reality once thought improbable, even impossible. A $100 million tech park sits atop former bean and corn fields, supporting a $2 billion naval technology facility dedicated to national security and preparing for a new dimension of innovation in microelectronics. All a far cry from a distant era where opportunity-sapping downsizing was a real threat.

Now, what’s on deck for the future? What great initiative will come tomorrow?

And how important is vision, especially in times were resources may be scarce, even non-existent? The late Dave Abel kept a framed ancient proverb in his office: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

By Michael Snyder, MEK